Strategic Channel Management of Saint Bernhard Winery: Direct Versus Indirect Sales

Marc Dressler

Keywords: Multichannel Management ● Wine Sales ● Customer Management ● Strategy ● Stakeholder Management.

Saint Bernhard Winery (SBW), located in the small wine region of “Hessian Bergstrasse” in Germany, had developed a strong multi-channel sales strategy, but lacked the desired profitability. The management was revisiting the channel strategy in the hopes of rectifying the situation. The CEO, Mr. Hoppe, had succeeded in stabilizing the company after years of management fluctuation. He managed to increase wine quality and revenue growth. Not an easy turn-around since SBW was a state-owned winery with 30 hectares and a history dating back to the 12th century. Mr. Hoppe pinned his hopes for growth in a mature market predominantly on indirect sales and added sales channels. Beyond an increase in revenues, the multi-channel approach secured a broader market beyond the winery’s local reach. This strategic marketing move seemed in line with a general market shift from “Direct To Consumer”-sales to indirect channels in the German wine market, but the marketing efforts did not yield the expected financial returns. A lack of profits, blamed on low production year after year, due to a variety of issues, drew the attention of the owners. Indeed, contracts with indirect sales channels partners required delivery at set prices even in situations where Saint Bernhard suffered from lower yields, less wine, and accordingly higher costs. Indirect sales channels had priority in delivery due to binding contracts, although private clients (DTC) were willing to pay higher prices. Indirect sales partners seemed an efficient sales opportunity, but Mr. Hoppe needed to deliver a revised multi-channel strategy securing sustainable profits.

For SBW, the DTC sales comprehended the store and a restaurant at the winery; a store at the monastery, where the lease ended and the owner (state of Hessen) wanted to foster its touristic value by inviting SBW to expand; online sales; and direct sales to the local business community. Hoppe considered building a new winery, possibly at the monastery site. The owners were reluctant, given the high investment needs and the disappointing profitability of the winery. Indirect sales, on the other hand, required fewer interactions. Successful negotiations safeguarded bigger sales volumes, but the retail counterparts were powerful. Once deals were closed, fulfillment of the contracts had priority. This results in a strategic trade off:

- Serving DTC clients to profit from premium prices meant acknowledging their need for an emotional buying experience that required adequate business models/offerings. Furthermore, this type of relationship was suffering from diminishing loyalty.

OR

- Using professional partners with buying power that needed compensation for their services in the form of substantial price discounts. Additional attention has to be paid to the risk of substitution as well as the pressure to fulfill negotiated contracts even in the case of a negative impact on profit and limited flexibility.

In order to concentrate on DTC and special wine retail, a future channel design might benefit by a shift from growth to profitability. Therefore, DTC offers the highest potential in price premium without minimal additional costs. DTC holds the possibility of securing a valuable long-term relationship with the clients. The contribution of the restaurant seems negligible. Management and sales capacity freed in case of reduced retail and discount efforts allows reallocation towards new store development at the monastery, the core element of sustainable sales for SBW. DTC activities offer great potential in case of an integrated e-Commerce strategy, asking for managerial attention. Local restaurants and business partners could be served as they are today. Expanding special wine retail sales bears several advantages. This channel represents a rather premium wine sales channel. The owners of the special wine stores engage for the wineries. Obviously a better lever for brand building than larger retailers or discount stores. The reduced but intensified sales channels allow to sell the output of the current 30 hectares, plus additional sourced wine production. Continuous pressure resulting the constant hope for high output could be relieved. As shown in the data provided in the case and supplementary arguments, discount, large retailers, independent agencies, and export increase complexity and reduce flexibility. Channel concentration provides the opportunity to optimize sales and managerial attention to the proprietary sales outlets to reach private consumers, a store relocation to attract new customers and optimize production, fostering internet sales, and reducing reliance on indirect sales.

In the aftermath of a low grape harvest threatening to meet retail contracts and potentially restricting product availability for private customers, Rainer Hoppe, chief executive officer of Saint Bernhard Winery (SBW) was under pressure from the ownership team to stabilize the business. A series of challenges had plagued the 2016 production year, beginning with heavy crop damage from a late frost and continuing with frequent summer rains requiring substantial spraying to prevent fungal diseases. Declining production but rising costs for crop protection affected profitability. Additionally, private customers complained about shortages of their favorite wines while retailers resisted price increases.

In late January 2017, two representatives from SBW’s ownership group met with Hoppe and demanded he sell off the 2016 inventory as quickly as possible. During that meeting, the owners denied Hoppe’s request for additional investments to modernize the marketing and sales capabilities of the winery. After the owners left, Hoppe thought to himself, “I need to revise SBW’s multi-channel marketing strategy.” He considered the options.

Should he allow the current lease agreement with the restaurant on SBW’s premises to expire, creating an opportunity to expand and refurbish the private client reception area? Or should he install a wine shop on the grounds of the monastery? Another possibility was to host more private events. How could he convince the owners to build a new winery facility? Was SBW putting too much emphasis on high-volume, low margin distributors? Finally, how might he go about export sales?

A WINERY WITH HISTORY

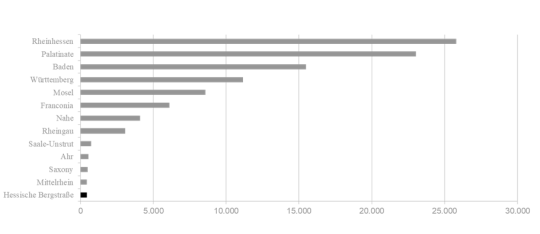

Founded by monks in 1138 as part of a Christian monastery, SBW was located in the German wine region of Hessische Bergstrasse (HB), in the state of Hesse. With less than 1,000 hectares of vineyards, HB belonged to the small German wine regions (See Exhibit 1). SBW had survived both historical upheavals (e.g. reformation, peasant wars, secularization, world wars …) and devastating natural disasters (e.g. phylloxera, an insect destroying the vines). In modern times, the ancient Saint Bernhard monastery had become a tourist attraction, with the winery as a separate entity.

Exhibit 1. German wine regions in 2016 (in hectares)

Source: DWI 2014

As a limited liability company, owned by the state of Hesse through a holding company, SBW was subject to the oversight of its supervisory board. The CEO of the holding company, Mr. Klein, and the deputy manager of the state of Hesse, Mr. Förster, were key board members. Mr. Klein´s background was in agriculture and Mr. Förster was a politician.

Although the winery had, in the past, focused on viticultural research, SBW now concentrated on wine production and sales, growing 15 varietals on 35 hectares and producing over 30,000 cases of Qualitätswein per year. Mr. Erler, the winemaker of SBW, explained, “… our clients expect and appreciate an extensive range of wine by varieties and styles. We therefore produce more than 50 different wines every year.”

The vertically integrated winery performed all steps in the value chain, from viticulture to wine production to marketing. However, they also sourced from third party growers for wine production. Wine yields in the northeastern German wine regions were typically much lower than the more productive western wine regions. The average German yield per hectare in 2014 was 92 hectoliters, while in HB it was only 69. Land was scarce. Planting was regulated and limited by the European Union. Limited yields effectively put a ceiling on German wine production limiting the output of the producers. Buying grapes, juice, or wine allowed producers to increase their output. SBW sourced grapes for about 12 percent of its wine production in 2016.

SBW’s production facility was not located at the monastery. It had been expanded and partially refurbished in 2002. The site offered a wine shop, a restaurant built in the 1980s, and a tasting room for up to 50 people. An additional wine shop was located at the old monastery. To reach the current production standards, SBW had made continuous investments in machinery, tools, and production infrastructure. Rainer Hoppe joined SBW as CEO in 2010 to end near continuous changes in the estate´s leadership. There had been four CEOs in four years. Mr. Hoppe had a background in both business and in the wine industry. Prior to the job at SBW, Hoppe had worked as a management consultant. His consulting and project management experience helped him tackle a series of operational and strategic challenges that began almost immediately upon accepting the post: the loss of SBW’s winemaker, a devastating flood that destroyed parts of the ancient wine cellars, and the state of Hesse restructuring their assets into a holding company.

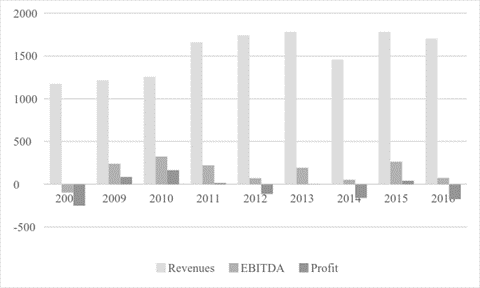

SBW’s disappointing financial situation and lack of profitability drew the attention of the owners (See Exhibit 2). Mr. Klein, in particular, stated, “… we are happy with the increase in revenues from 1.1 million Euros in 2007 to 1.7 million in 2016, but we expected profits to increase accordingly.” Mr. Hoppe explained that low yields had affected profitability. Each of the previous years each had its own challenge to yields: hail, frost, heavy precipitation, too much heat, and the insect drosophila suzukii (a vinegar fly), among others. He also referenced the price sensitivity of German consumers limiting the options to increase profitability.

Exhibit 2. SBW- financial results (in 1,000€)

Source: (sanitized company data, 2017)

Mr. Hoppe highlighted the need for investment to raise both quality and brand recognition of the winery. He proposed to either substantially upgrade the current production and sales facilities or to build a new winery. The state of Hesse was considering ways to upgrade the monastery to increase its touristic value. State representatives had approached SBW to consider investing in a new sales store or even relocating production back to the monastery.

In order to show the potential of new production and sales facilities, Mr. Hoppe organized trips with his board members to visit benchmark wineries. Mr. Klein was strongly impressed by the restructuring of the larger state winery of Hessen, Kloster Eberbach, which also historically belonged to a monastery. Their success supported Mr. Hoppe´s argument to consider building a new facility; however, the new winery at Kloster Eberbach had cost more than 15 million Euros.

COMPETITIVE ENVIRONMENT IN A MATURE MARKET

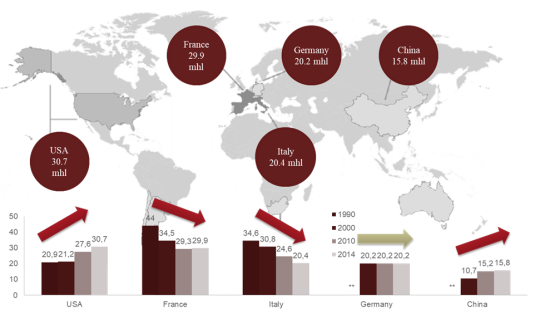

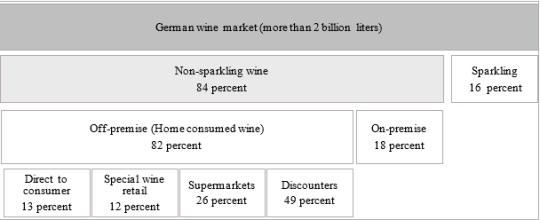

Klein, Förster, and Hoppe all agreed that the German wine market had a great deal of potential. Germany ranked fourth in global wine consumption, with sales of more than two billion liters of wine annually (See Exhibit 3). According to the Deutsches Weininstitut (DWI), German wine accounted for only 45 percent of that consumption.

Exhibit 3. Global wine consumption in million hectoliters (mhl/year) and per capita

Sources: DWI, DWV, and OIV, 2014 - 2017

Historically, German wines had an international reputation for quality, but in the 1960s and 1970s, German wine had lost some of this because of mass production and cheap, sweet wines - e.g., Liebfrauenmilch. In recent years, excellent Rieslings and increasingly valued Pinot Noirs had reestablished the global quality of German wines. According to Deutscher Weinbauverband (DWV), the German Winegrowing Association, German wine exports in 2016 totaled one million hectoliters (out of a total production of 7-10 million hectoliters) with a trend of increasing prices, but diminishing volumes.

With annual revenues of more than one million Euros, SBW belonged to the population of larger German wineries. Of the more than 40,000 vintners cultivating grapes in Germany, the average plot size was less than five hectares of vineyards and most wine producers averaged less than 500,000€ of revenues a year.

Mr. Klein, drawing on his agricultural experience with other crops, proposed leveraging their relative size to exploit economies of scale and scope. Mr. Hoppe, however, countered that even larger wineries, more than triple the size SBW, were doing that already. Additionally, he was concerned that emphasizing size might negatively affect attempts to position the winery as a higher end quality producer. Mr. Hoppe perceived SBW to be trapped between larger wineries with economies of scale, often organized as cooperatives, and smaller vintners, perceived to be more charming and delivering outstanding terroir-based wines. “We are too big to rely exclusively on DTC sales. But, for the very price sensitive indirect channels we are struggling on the cost side, competing with providers owning up to 250 hectares or cooperatives with more than 500 hectares of wine under production.”

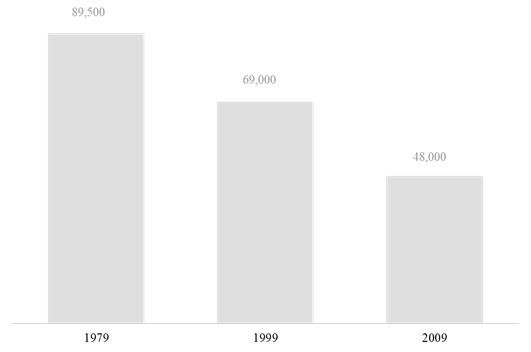

Mr. Hoppe recognized a massive shift in the German wine industry. Overall production capacity was about 100,000 hectares of vineyards. The supplier pool had diminished drastically, with half of the traditional winegrower population leaving the business (See Exhibit 4). For Mr. Hoppe, the grower exodus illustrated the challenging market situation.

Exhibit 4. Wine producers in Germany

Source: BMELV 2012

Wine consumers enjoyed a rich world of brands, easily accessible in outlets ranging from specialized wine retailers to convenience stores. More than 10,000 German labels and at least the same number of international brands competed for consumer attention. Indirect sales channels (supermarkets, discount stores, and specialized wine retailers) supplied more than 70 percent of the German wine demand (See Exhibit 5). Buyers welcomed the advantages offered by retailers: reliable and extended opening hours (compared to the wineries´ shops), one-stop shopping, attractive pricing, and additional services for example home delivery or loyalty programs. Many retailers also provided a wide variety of wines: a portfolio of more than 1,000 different wines was not unusual. Increasingly, retailers used wine as a category to attract customers. Also because of low prices, discount stores steadily increased their market share of wine sales. Consumer studies (e.g., DWI, GfK …) forecasted that German consumers further shift from direct purchases at the wineries to indirect provision.

Exhibit 5. German wine sales 2014

Source: DWI 2017

Discounters, supermarkets, and imported products kept wine prices down. Most wine sales in discounters and supermarkets were in the range of two to four Euros per bottle. Discounters´ average wine sales price was 2.50 € per liter of wine. An international price study (OC&C) reported that 56 percent of German consumers reacted to price increases by substituting out either the product or the supplier. Global average for substitution was less than 40 percent, and for UK or USA only 35 percent of the consumers switched product.

On-premise consumption made up about one-fifth of the German wine market. Restaurants either sourced directly from the wine producers - with a regional focus - or indirectly via agencies or distributors.

More than two million hectoliters of wine sold directly from the estates to the consumers (direct to consumers - DTC). This historic sales channel depended on an open-door policy with visits, taste, buy, and pick up by customers. Obviously, tourism nourished these wine sales. Internet impacted all channel sales but provided an additional sales channel. Wineries pursued online sales directly and indirectly via specialized internet platforms or through online offers from the retail partners. Experts forecasted high growth of internet wine sales.

SALES APPROACH AND MARKETING

As CEO at SBW, Mr. Hoppe had opted for a multichannel approach. He seized opportunities to extend SBW´s reach beyond regional focus by selling to supermarkets, discounters, and specialized wine retail stores. Mr. Förster strongly favored DTC sales, predicting “the comparatively low wine consumption in Hessische Bergstrasse will increase over time.” Hoppe argued that “even with an increasing wine consumption, consumers tend to opt for wines of other regions or international ones because of curiosity.” Hoping to keep up with the changing environment, Hoppe also created an infrastructure to sell via the internet to keep contact with customers, which is jeopardized when using third-party internet sales platforms.

Private customers were the cornerstone of SBW´s business model, purchasing wine either on-site at the winery, at the shop in the former monastery, by mail order, or online. The proximity to metropolitan areas (Frankfurt, Darmstadt and Mainz) and their visitors allowed SBW to extend its reach beyond local consumers. SBW´s customer database contained more than 6,000 addresses of private customers from all over Germany as well as abroad. Ms. Weltmann, responsible for marketing, described the average private customer as “47 years old, married and conservative, with 65 percent of the clients being located within 150 km.” SBW contacted this client base at least once a year by a letter and e-mail informing them about new products and prices. Sending the product list stimulated online orders from more distant clients and motivated them to visit the winery. Orders were processed and packaged in-house, then shipped by post. Pricing for online orders did not differ from pick-ups at the winery. With a minimum of 150€, online orders were delivered free of charge.

As Hessische Bergstrasse developed as a tourist destination, additional visitors were expected. The marketing efforts of the region focused on the pleasant climate, a scenic countryside, medieval cities, outdoor sports offerings, and wine production.

In addition to DTC sales, SBW served business to business (B2B) channel in regional businesses and local restaurants. B2B sales were predominantly seasonal with businesses ordering Christmas presents for their clients. SBW perceived the B2B customer group as not price sensitive. Processing and distribution were charged at cost. Local restaurants, the second group of B2B clients, were highly regarded not only as a revenue stream, but also as source for new customers. SBW did not track the “referral process” from restaurants to the winery, but the team was convinced there was an impact. Serving the local restaurants supported regional networking, but some partners extended their payments for the delivered goods beyond contractual agreements, lacking financial liquidity.

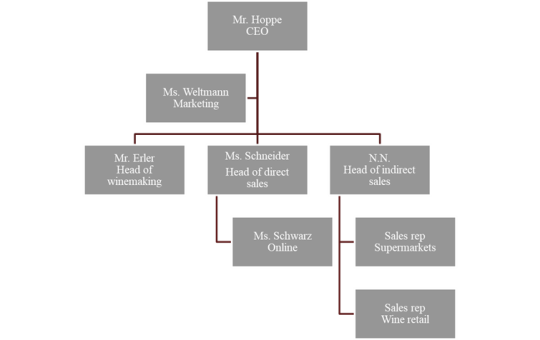

SBW’s sales and marketing team consisted of six people. Ms. Schneider was responsible for the direct business (SBW sales facilities, SBW online shop, B2B, the on-site restaurant). Ms. Schwarz, a young professional handling the online interaction and all back-up processes for client relation, supported her. Mr. Hoppe temporarily filled a vacant position as head of indirect sales, negotiating with the German retail chains, visiting specialized wine retail stores, and interacting with wine sales agents and online wine shops. Two sales representatives supported Mr. Hoppe, who coordinated the sales team. Marketing was in the hands of Ms. Weltmann, reporting directly to Mr. Hoppe. Export experience within the team was very limited and export was not actively pursued. See Exhibit 6 for the organization chart.

Exhibit 6. SBW organization

Source: Sanitized company data, 2017

Once a year SBW celebrated a one-day “open cellar event” extending an invitation to predominantly private customers to taste the new wines. SBW also participated in an annual regional wine weekend festival. For the indirect channels, yearly contract negotiations with the supermarkets and discounters were of paramount importance. In regard to the specialized wine retailer shops, the team tried to visit the larger partners in metropolitan areas once a year. Additionally, SBW participated in the international wine fair “ProWein” in Düsseldorf.

“Tradition and progress” were the core terms in the company´s communication. External communication focused on the products, terroir and the vineyards. A product pyramid informed consumers about the four level product range for white and red wines. Basic wines built the lower part of the pyramid, high-end products the top. Pricing started at 3.50€ for the lower products and went up to 30€ for the premium products. Premium products were late harvest wines or red wines fermented in costly oak barrels. The flyer described every product briefly with grape variety, vintage, production, terroir, sensory characteristics and any awards. The left side of the triangle represented white and the right side the red wines. Exhibit 7 highlights a product belonging to the basic white wine portfolio.

Exhibit 7. Saint Bernhard´s visual product structuring

Mr. Hoppe strongly supported developing the quality of the wine. Official German wine tastings and success in wine competitions honored wine quality and fostered reputation. Stickers on the wine bottles and references in the price list informed customers about award winning wines. The estate produced their wines ecologically, but the winery was not eco-certified. Mr. Erler explained that being located in the north required flexibility to react to weather and vegetation, a barrier for certification. Despite a strong commitment for the regional community, longstanding existence, and reliance on renewable energy, SBW did not seek a certification to uphold claims of sustainability (i.e. longstanding business performance considering ecological, social, and economic perspectives) actively. The certification process required costly audits and would limit managerial flexibility. Mr. Hoppe also realized that “sustainability” would not necessarily yield the profitability he sought.

REVENUE GENERATION

Private clients paid full list prices. Channel partners received discounts ranging from five to 50 percent of the list price, without a set pricing scheme by client. The individual price reductions reflected the market power of the channel partner. Such a pricing strategy was common practice in the industry. Indeed, prices of the regional competitors provided orientation for SBW´s price levels. SBW raised prices by fifteen cents up to one Euro per bottle annually. The internet jeopardized the longstanding business practices with increased transparency. Private clients were now able to check sales prices via internet platforms. Channel partners could not only inform themselves about end consumer pricing, but also estimate pricing conditions by surfing the web.

SBW generated supplementary revenues with their restaurant and sales of regional food and wine related merchandise. A gastronomic partner rented the winery's restaurant on a long-term basis, securing stable income. All wines on the restaurant menu were restricted to SBW estate.

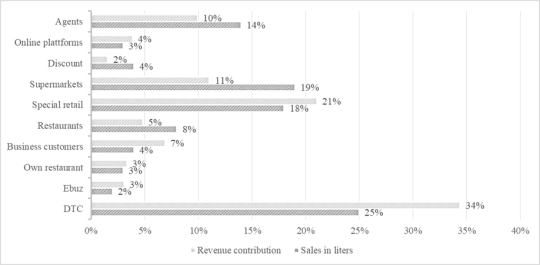

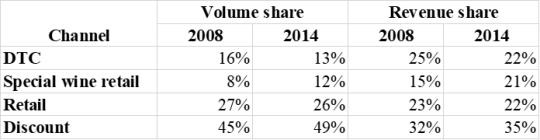

Mr. Hoppe asked his team for an overview of volume and revenue broken down by channel to discuss with his board. Ms. Schneider gathered the data (See Exhibit 8):

Exhibit 8. SBW - Sales and revenue generation by channels in 2016

Source: sanitized company data, 2017

CHANNEL OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS

Mr. Hoppe had strongly advocated for the current positioning and client portfolio. He felt that expansion of indirect sales had allowed the winery to grow. The indirect channel partners guaranteed larger volume sales to clear yearly production. Those channels secured welcomed financial liquidity and helped avoid capacity limitations in storage. Furthermore, indirect channel partners helped gain market share (See Exhibit 9). Efficient sales with few interactions and negotiations resulted in substantial revenues. Special retail stores in Germany enabled SBW to reach distant clients and to be present in the market characterized by a higher price level. When traveling and visiting wine shops in other areas of Germany, Mr. Hoppe enjoyed having SBW´s products on the shelves of the shops. He was also proud of seeing his wines on the menu of some distinguished restaurants nationwide.

Exhibit 9: Wine sales in Germany by market channel

Source: DWI 2011& 2017

Ms. Schneider was concerned that indirect sales with the retailers’ professionalism to squeeze margins influenced SBW´s profitability: “Indirect clients are only incentivized by price discounts we don´t have to grant private customers.” Mr. Hoppe referred to the higher volume of wine sales that are possible with few negotiations with retail chains. Ms. Schneider emphasized, “… the power of the indirect channel partners does not only reflect in the prices realized. In times of lower yields the retailers request fulfillment of signed contracts. Private clients suffer as retail chains have priority in delivery. I have simulated our sales projecting only 70 percent of the current yield. If we were required to deliver the wine volumes to the retail chains as negotiated, direct sales would drop from 53 percent to 26 percent. We would not only suffer from 30 percent missing sales, but additionally our average price would decrease by more than 10 percent.”

Ms. Weltmann contributed from a marketing perspective: “In my opinion, we have gained a very solid brand and sales base with limited marketing so far. One needs to recognize that our marketing efforts are product-centric directed towards end-customers. The retail chains are very price sensitive and do not really appreciate our efforts on product quality improvement, nor are they interested in our marketing efforts. Still, we need to do all the efforts not only for the end-customers but also to have a story that differentiates us in the market. We can´t live exclusively on either DTC nor on indirect sales. Our marketing efforts serve both directions.”

Mr. Hoppe reminded, “… on the other hand, DTC sales of wineries are diminishing as is customer loyalty. While it is still common that consumers pick up at the winery or have wine delivered personally to their homes, we are experiencing a decrease in loyalty from the end-customer client base.” Ms. Weltmann was convinced SBW would “be able to counter that trend. We should optimize the web page and be more active in social media. Our online shop still offers potential for growth. We can provide a unique buying experience for the clients. If we invest in the show rooms and facilities for our winery and offer special events, we will keep the clients happy and attract new customers. And again, private customers for us are the lever for profitability.” DTC promised higher revenues, but also incurred costs. SBW private consumers´ demographics and internet competition were sources of risk for the revenues. Although the global population was

increasing, in Germany the growth rate was negative. Hence, fewer consumers needed to consume more wine to keep the market stable. This did not look likely, given the wine consumption trends of the neighboring nations France, Italy, and Spain, where wine consumption was continuously dropping with diminishing alcohol consumption. In addition, looking at their own client portfolio, Saint Bernhard needed to win new and younger customers. Internet provided unpredictable transparency and the convenience of buying from home could hamper consumer loyalty to the providers in the future. Curious customers might try products of the competitors. Internet sales platforms offered a great opportunity to sell surplus stocks at special deals, but was that sustainable?

Mr. Hoppe, supportive that direct sales allowed for higher prices, asked the team to acknowledge that Ms. Weltmanns’ customer happiness requires adequate sales activities and care for the customers. The team discussed the pricing. All were happy about the average price of 5.80 euros for a liter, yielding 4.50 euros for a bottle of wine. The massive discounts for the retail chains, ranging from 20 to 50 percent of the net sales prices were a nuisance. Mr. Hoppe remembered his unpleasant last meeting with REWE. Despite a longstanding partnership, he felt ignored when presenting his needs. As always, the category managers of REWE let him wait for an hour. He then entered a large room, faced five representatives, was not offered coffee or any other drinks. During the meeting in early December, he placed a request for a price premium: “Our costs to deliver the promised wine quality in 2016 exceeded the regular costs of production. No one could predict such an extended period of rain. We needed five times the normal spraying trips to fight fungal infestation but cannot compensate with higher yields.” Mr. Bauer, one of the five attendant category managers from REWE, reacted. Mr. Bauer stated in a calm but determined way: “I am surprised since in the course of the preceding negotiations the costs of production have never been an argument. Mr. Hoppe, we are neither willing nor able to compensate for your managerial deficits. Please acknowledge that we have an extensive list of wineries that want to become our partners. If you don’t intend to stick to the negotiated contracts, we need to substitute the shelf place of your winery.” Mr. Schmidt, a second representative from REWE added, “I support my colleague´s arguments with reference to the spot prices for German wine. They are very low now. Am I therefore right that with higher costs across all wine producing regions, but lower prices for the wine, we have paid too high of prices in the past?” Mr. Hoppe was not interested in continuing that line of discussion. He recalled that wine journals reported a current eagerness of retailers to increase transparency of the costs of wine production and the profitability of their suppliers. Such insights destroyed every loophole for margins for suppliers. He, therefore, gave up on renegotiating higher prices and nodded to Mr. Bauer´s statement of “good relationship that should not be jeopardized and that SBW needs to deliver to the agreed terms.”

Considering his levers to influence profitability, Mr. Hoppe realized that price increases might certainly help. The interaction with Messrs. Bauer and Schmidt was not promising for price increases in indirect sales. What about the private clients? Ms. Weltmann insisted that the clients

know what they have paid in the past and that they are price sensitive. Mr. Hoppe asked a consultant, Mr. Köhne, for advice on pricing. Based on a market screening, Mr. Köhne confirmed that in a quality-price benchmark, wines from HB seemed to be in line with quality expectations. Mr. Köhne concluded not to increase prices since SBW´s prices were higher than most of the regional competitors.

LOOKING AHEAD: NEED TO REDIRECT THE CHANNEL STRATEGY?

Rainer Hoppe concluded that he might need to redesign the sales approach and the channel management. Should SBW move forward with a stronger emphasis on sales to private customers, potentially allowing for further price increases? Should he aim for more volume production with a strong focus on indirect sales via retail chains? Despite experts touting growth options in other countries, he acknowledged the missing export experience and high costs to refrain from export efforts, but perhaps that is shortsighted?

The marketing, sales, and channel strategies also needed to consider the corresponding investment needs. Reorienting on private German consumers required investments. The sales rooms were not fancy. Does the upcoming end of the lease agreement with the restaurant open a window of opportunity to cancel the contract to then refurbish the private client reception and allow additional sales? Would investments in a new wine shop on the grounds of the monastery with a possible relocation of the winery pay off? Would the owners support the construction of a new winery? While retail allowed SBW to sell larger volumes efficiently across multiple regions, did the retailer`s market power represent a high risk for the future? Klein and Förster expected the strategic options with corresponding business implications in detail to clarify the marketing and sales roadmap for the future.

Endnotes

________________________